Political cartoons are not merely humorous sketches; they are acts of democratic reasoning that question power, provoke debate, and preserve public conscience. This understanding became deeply profound in me once again as I turned over the pages of a book on cartoons and caricatures during a recent visit to my university library where, as a student, I had preferred to immerse my intellect among books, magazines, and newspapers. I returned to the sanctuary of my alma mater almost two decades after leaving it. In retrospect, a churn of memories recalls those intellectually overwhelming satirical images from cartoons that appeared in newspapers and periodicals that I had enthusiastically preserved in my photographic memory. The university library had been my habitual habitat, where I first experienced waves of intellectual insight washing over the shores of my conscience – and I, a novice, reduced to perplexity by the enormity of the wonderful books, periodicals, and dailies, yet irresistibly captivated by their intoxicating fragrance of undusted antiquity.

Though I am neither a cartoonist nor a caricaturist, political cartoons and caricatures have always kept my socio-political curiosity tightly fastened to controversial thoughts and critical events. These art forms have been powerfully used as mediums to communicate the most sensitive issues, and they became even more influential in many countries through their transition from authoritarianism to democracy. Highly thought-provoking and capable of capturing the public conscience, they often proved sharper than the might of spoken words or expansive vocabulary.

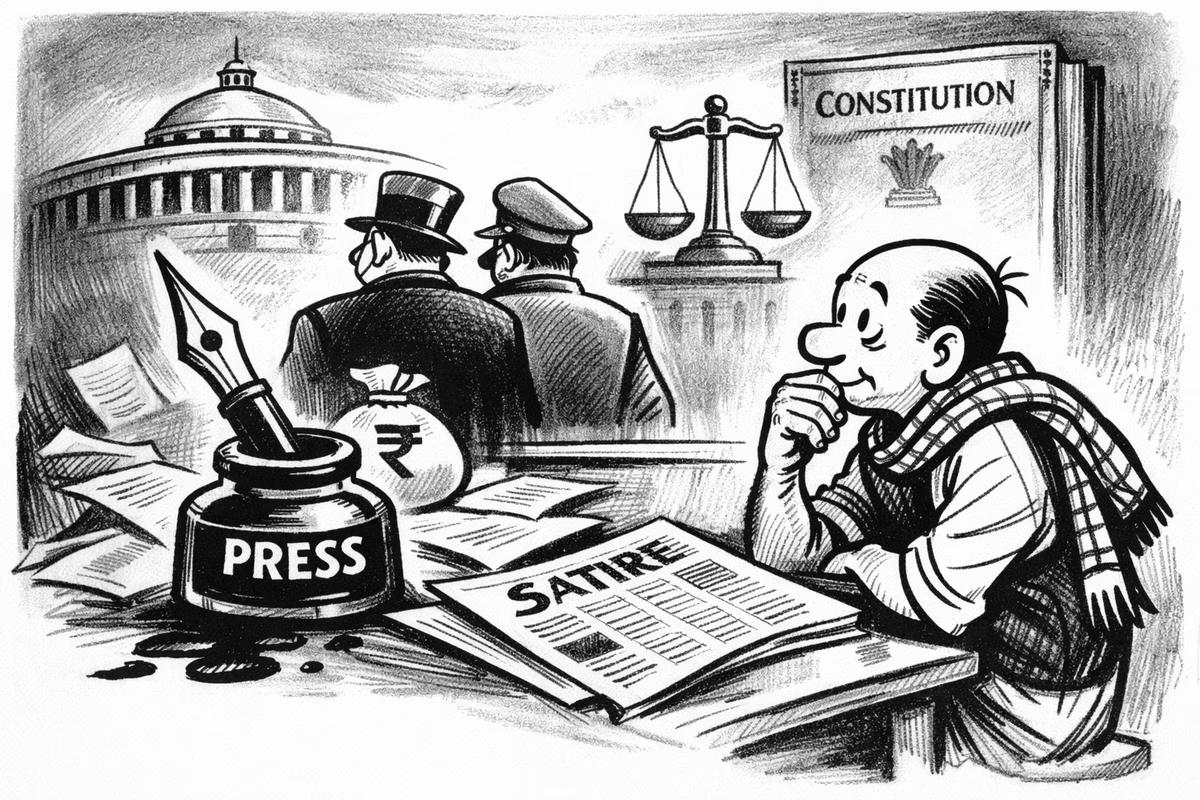

Meticulously crafted with wit, exaggeration, and sharp symbolism, these humorous visual formats—cartoons and caricatures—have long served as incisive tools of social commentary, criticism, and political resistance. Perhaps their intense ability to communicate the most grueling subjects with indisputable sarcasm is the reason I have always loved them. They invite deeper reflection and discussion about the depth and veracity with which they express public sentiment, as well as their power to shape political discourse while challenging the authority of the ruling class.

India under British colonial dominance witnessed strong resistance from cartoonists, who fearlessly questioned the ruthlessness of British rule through anti-colonial satire. Gaganendranath Tagore is regarded as the pioneer of political caricature in India. He questioned colonial arrogance and also critiqued Indians for their blind imitation of Western culture. As a political cartoonist, his albums, Realm of the Absurd and Reform Screams stand out prominently.

K. Shankar Pillai, popularly known as Shankar, was one of the brightest figures among the galaxy of Indian cartoonists. His life epitomized the growth of political cartooning in India. Shankar was born in Kayamkulam, Kerala, on 31 July 1902. Beginning his career as a cartoonist at The Hindustan Times, Shankar soon shot to fame. The satirist in him caricatured everyone from British Viceroys to leaders like Muhammad Ali Jinnah and other political figures.

Mahatma Gandhi is known to have sent a note of disagreement to Shankar regarding his criticism of Jinnah through cartoons. Gandhi advised him that his portrayals should not be vulgar and should not “bite” the person being targeted. Jawaharlal Nehru, on the other hand, was fascinated by Shankar’s satirical communication through cartoons. Shankar featured Nehru in more than 4,000 cartoons. The impact of Shankar’s incisive caricatures on Nehru was so profound that he often sent them to his daughter, Indira Gandhi.

Shankar rose to greater prominence through Shankar’s Weekly, which he established in 1948 and ran until 1975. The magazine was forced to shut down when India, under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, endured the horrors of the Emergency. R. K. Laxman and many other cartoonists of similar stature used Shankar’s Weekly as their launch pad.

Bal Thackeray, before beginning his career as an aggressive politician, started out as a cartoonist at the Free Press Journal in Mumbai. His cartoons largely addressed Marathi identity and regional pride. He faced accusations of being a crusader of regionalism, as his cartoons often targeted minorities, thereby normalizing political aggression. The use of cartoons not merely as satire but as political weapons was unique to Thackeray.

R. K. Laxman, however, chose not to follow aggressive satire. His ‘quiet’ satire remained powerful through his iconic creation, the “Common Man,” who stood as a silent witness to the duplicity of politicians and the ruling establishment. His cartoons carried suggestions, warning signals, and even firm indicators for correction.

There were several instances of cartoonists being thrown behind bars for being piercing and satirical toward the government. The Emergency witnessed the government’s ruthless clampdown on the media, and cartoons came under severe attack for lashing out at the corridors of power. Abu Abraham, popularly known as Abu, was among those who came down heavily on the Indira Gandhi establishment.

One of his iconic Emergency-era cartoons depicted President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed signing the proclamation from a bathtub, symbolizing the haste and rashness with which the draconian law was enforced. India was literally pressed hard under the heavy blanket of the Emergency, suffocating democratic freedoms, while the press was forced into silence and throttled. Abu’s cartoons were strictly political and remained uncompromisingly unbiased.

India, at present, is deeply engaged in debates on freedom of expression, and cartoons often crash headlong into the faces of the powerful. Cartoonists and even those who merely appreciate or share cartoons can sometimes find themselves trapped in unpleasant legal battles and prolonged harassment. Drawing or sharing cartoons on social media can invite hazardous legal trauma.

India is often described as having a curtailed media fraternity, with media across countries accusing both state and central ruling establishments of being punitive toward freedom of expression. This may not be entirely true. Yet, beyond the ordinary, there are troubling instances of radicalization displaying unruly aggression toward the media. Events such as the Charlie Hebdo attack in France in 2015 stand as grim reminders of how violently dissent can be silenced.

Freedom of expression, however, also demands restraint while articulating disagreement. Sharp criticism should not rob society of its sanity by misleading it. Cartoons must prevail and continue to blow the whistle through satire and sarcasm.

As I put the book on cartoons and caricatures into one of the dusty shelves of my university library, the alumnus in me travels vigilantly back in time once again, flipping through the pages of Malayala Manorama, Mathrubhumi, and The Indian Express in my memory. I see, without the least distortion, the finest cartoons of my university days by stalwarts like Yesudasan, Gopikrishnan, Toms and many others, all smirking back at me. They exposed the duplicity of leaders, strongly admonished the dishonesty of people, and gently warned society against its own lackadaisicalness. As someone rightly said, a good cartoonist is a reporter who uses pictures instead of words.